Graph Laplacian Fundamentals

Graphs encode relationships between objects, but to apply the powerful machinery of linear

algebra — eigenvalues, quadratic forms, spectral decompositions — we need a matrix that

faithfully represents a graph's connectivity structure. The graph Laplacian

is exactly this matrix. It captures how "different" adjacent vertices are from each other,

making it the natural bridge between

graph theory and

spectral analysis.

Definition: Unnormalized Graph Laplacian

For a graph \(G\) with adjacency matrix \(\boldsymbol{A}\) and degree matrix \(\boldsymbol{D}\),

the unnormalized graph Laplacian is the matrix

\[

\boldsymbol{L} = \boldsymbol{D} - \boldsymbol{A}.

\]

Its entries are given by

\[

L_{ij} = \begin{cases} \deg(v_i) & \text{if } i = j \\ -1 & \text{if } i \neq j \text{ and } v_i \sim v_j \\ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}

\]

where \(v_i \sim v_j\) means vertices \(v_i\) and \(v_j\) are adjacent.

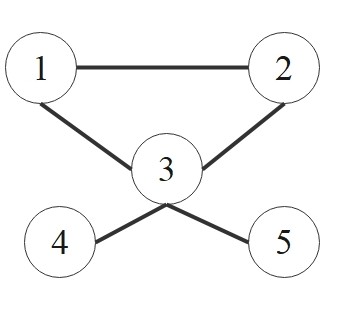

Example:

\[

\underbrace{

\begin{bmatrix} 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 2 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 4 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{bmatrix}

}_{\boldsymbol{D}}

-

\underbrace{

\begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

1 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

\end{bmatrix}

}_{\boldsymbol{A}}

=

\underbrace{

\begin{bmatrix} 2 & -1 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\

-1 & 2 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\

-1 & -1 & 4 & -1 & -1 \\

0 & 0 & -1 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{bmatrix}

}_{\boldsymbol{L}}

\]

The Laplacian Quadratic Form (Measuring Smoothness)

The definition \(\boldsymbol{L} = \boldsymbol{D} - \boldsymbol{A}\) may appear

arbitrary, but the Laplacian has a natural interpretation through its quadratic form,

which measures how much a signal varies across the edges of the graph.

Theorem: Dirichlet Energy

For any signal \(\boldsymbol{f} \in \mathbb{R}^n\) defined on the vertices of a

graph with Laplacian \(\boldsymbol{L}\), the quadratic form satisfies

\[

\boldsymbol{f}^\top \boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{f} = \sum_{(i,j) \in E} w_{ij}(f_i - f_j)^2

\]

where \(w_{ij}\) is the weight of edge \((i,j)\) (equal to 1 for unweighted graphs).

This quantity is called the Dirichlet energy of \(\boldsymbol{f}\).

The Dirichlet energy is small when adjacent vertices have similar signal values (the signal

is "smooth") and large when adjacent vertices differ significantly. The Laplacian thus acts

as an operator that measures the total variation of a signal across the graph's edges.

Since \(\boldsymbol{f}^\top \boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{f} \geq 0\) for all \(\boldsymbol{f}\),

this also shows that \(\boldsymbol{L}\) is

positive semidefinite.

Insight: Dirichlet Energy as a Regularizer in ML

The Dirichlet energy \(\boldsymbol{f}^\top \boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{f}\) is widely used as a

graph regularization term in semi-supervised learning. The objective

\[

\min_{\boldsymbol{f}} \|\boldsymbol{f} - \boldsymbol{y}\|^2 + \alpha \, \boldsymbol{f}^\top \boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{f}

\]

penalizes label assignments where connected nodes receive different labels, encoding the

smoothness assumption: nearby nodes in a graph are likely to share the same label.

This principle underlies label propagation, graph-based semi-supervised learning, and the

message-passing mechanism in Graph Neural Networks.

Normalized Laplacians

The unnormalized Laplacian \(\boldsymbol{L}\) can be biased by vertices with

large degrees, since high-degree vertices contribute disproportionately to the

Dirichlet energy. To account for varying degrees, two normalized Laplacians

are commonly used.

Definition: Normalized Graph Laplacians

1. Symmetric Normalized Laplacian:

\[

\mathcal{L}_{sym} = \boldsymbol{D}^{-1/2} \boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{D}^{-1/2} = \boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{D}^{-1/2} \boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{D}^{-1/2}

\]

This is a symmetric matrix with eigenvalues in the range \([0, 2]\).

2. Random Walk Normalized Laplacian:

\[

\begin{align*}

\mathcal{L}_{rw} &= \boldsymbol{D}^{-1} \boldsymbol{L} \\\\

&= \boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{D}^{-1} \boldsymbol{A} = \boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{P}.

\end{align*}

\]

Here, \(\boldsymbol{P} = \boldsymbol{D}^{-1}\boldsymbol{A}\) is the transition matrix of a random walk.

Thus, the eigenvalues of \(\mathcal{L}_{rw}\) relate directly to the convergence rate of the random walk.

Both normalized forms share the same eigenvalues. The choice between them depends on the application:

\(\mathcal{L}_{sym}\) is preferred when symmetry is needed (e.g., for the spectral theorem),

while \(\mathcal{L}_{rw}\) connects directly to random walk analysis.

Spectral Properties

The Dirichlet energy established that \(\boldsymbol{L}\) is positive semidefinite, which

immediately constrains its eigenvalue structure. Since \(\boldsymbol{L}\) is also real and

symmetric, the spectral theorem guarantees a

complete set of real, nonnegative eigenvalues and orthonormal eigenvectors. These eigenvalues

and eigenvectors encode remarkably detailed information about the graph's connectivity.

The eigendecomposition of the unnormalized Laplacian \(\boldsymbol{L}\) is:

\[

\boldsymbol{L} = \boldsymbol{V}\,\boldsymbol{\Lambda}\,\boldsymbol{V}^\top,

\quad

\boldsymbol{\Lambda} = \mathrm{diag}(\lambda_0, \lambda_1, \dots, \lambda_{n-1}),

\]

with ordered eigenvalues

\[

0 = \lambda_0 \le \lambda_1 \le \cdots \le \lambda_{n-1},

\]

and orthonormal eigenvectors \(\boldsymbol{v}_0, \dots, \boldsymbol{v}_{n-1}\)

(which form a basis for \(\mathbb{R}^n\)).

The Smallest Eigenvalue (\(\lambda_0\))

The smallest eigenvalue \(\lambda_0\) is always 0. Its corresponding eigenvector

is the constant vector \(\boldsymbol{v}_0 = \boldsymbol{1}\) (a vector of all ones).

\[

\boldsymbol{L}\boldsymbol{1} = (\boldsymbol{D} - \boldsymbol{A})\boldsymbol{1} = \boldsymbol{D}\boldsymbol{1} - \boldsymbol{A}\boldsymbol{1} = \boldsymbol{d} - \boldsymbol{d} = \boldsymbol{0}

\]

(where \(\boldsymbol{d}\) is the vector of degrees).

Definition: Eigenvalue Multiplicity and Connectivity

The multiplicity of the zero eigenvalue (how many times \(\lambda_k = 0\))

is equal to the number of connected components in the graph. For any

connected graph, \(\lambda_0 = 0\) is a simple eigenvalue, meaning \(\lambda_1 > 0\).

The Fiedler Vector and Algebraic Connectivity

While \(\lambda_0 = 0\) tells us whether the graph is connected (and how many components it has),

the second-smallest eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) quantifies how well the graph is connected.

It is arguably the single most informative spectral quantity of a graph.

Definition: The Fiedler Vector and Algebraic Connectivity

The eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) is called the algebraic connectivity

(or Fiedler value) of the graph.

- \(\lambda_1 > 0\) if and only if the graph is connected.

- A larger \(\lambda_1\) indicates a more "well-connected" graph (less of a "bottleneck").

The corresponding eigenvector \(\boldsymbol{v}_1\), known as the Fiedler vector,

is central to spectral clustering. The sign of its entries (+/-) provides a natural

partition of the graph's vertices into two sets, often revealing the graph's weakest link.

The Spectral Gap and Cheeger's Inequality

The Fiedler value \(\lambda_1\) provides a spectral measure of connectivity, but

one might ask: does it correspond to a genuine combinatorial notion of "bottleneck"?

Cheeger's inequality makes this connection precise, relating the spectral gap to the

minimum normalized cut of the graph.

Theorem: Cheeger's Inequality

Let \(h(G)\) be the Cheeger constant (or conductance), which measures the "bottleneck"

of the graph by finding the minimum cut normalized by the volume of the smaller set:

\[

h(G) = \min_{S \subset V} \frac{|\partial S|}{\min(\text{Vol}(S), \text{Vol}(V \setminus S))}

\]

where \(\text{Vol}(S) = \sum_{v \in S} \deg(v)\).

Cheeger's inequality bounds the second eigenvalue \(\lambda_1\) of the normalized Laplacian

(\(\mathcal{L}_{rw}\) or \(\mathcal{L}_{sym}\)) using this constant:

\[

\frac{h(G)^2}{2} \leq \lambda_1 \leq 2h(G)

\]

This fundamental result links the spectral gap directly to the graph's geometric structure: a small \(\lambda_1\)

guarantees the existence of a "bottleneck" (a sparse cut), while a large \(\lambda_1\) certifies that the graph

is well-connected (an expander graph).

Insight: The Spectral Gap in Network Science and ML

The spectral gap \(\lambda_1\) has direct practical significance. In graph-based semi-supervised learning,

a large spectral gap means that label information propagates quickly through the graph, leading to better generalization

from few labeled examples. In network robustness, \(\lambda_1\) measures how resilient a network is to

partitioning - networks with small algebraic connectivity are vulnerable to targeted edge removal. The Cheeger

inequality thus provides a principled criterion for evaluating graph quality in applications from social network analysis

to mesh generation in computational geometry.

Graph Signal Processing (GSP)

The GSP framework provides a crucial link between graph theory and classical signal analysis. It

re-interprets the Laplacian's eigenvectors as a Fourier basis for signals on the graph,

making it the natural generalization of the classical

Fourier transform to irregular domains.

Definition: Graph Fourier Transform (GFT)

Let \(\boldsymbol{V} = [\boldsymbol{v}_0, \boldsymbol{v}_1, \ldots, \boldsymbol{v}_{n-1}]\)

be the matrix of orthonormal eigenvectors of \(\boldsymbol{L}\).

For any signal \(\boldsymbol{f}\) on the graph, its Graph Fourier Transform

(\(\hat{\boldsymbol{f}}\)) is its projection onto this basis:

\[

\hat{\boldsymbol{f}} = \boldsymbol{V}^T \boldsymbol{f}

\quad \text{(Analysis)}

\]

And the inverse GFT reconstructs the signal:

\[

\boldsymbol{f} = \boldsymbol{V} \hat{\boldsymbol{f}} = \sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \hat{f}_k \boldsymbol{v}_k

\quad \text{(Synthesis)}

\]

The eigenvalues \(\lambda_k\) represent frequencies:

-

Small \(\lambda_k\) (e.g., \(\lambda_0, \lambda_1\)) \(\leftrightarrow\) Low Frequencies:

The corresponding eigenvectors \(\boldsymbol{v}_k\) vary slowly across edges

(they are "smooth").

-

Large \(\lambda_k\) \(\leftrightarrow\) High Frequencies:

The eigenvectors \(\boldsymbol{v}_k\) oscillate rapidly, with adjacent

nodes having very different values.

This frequency interpretation connects back to the Dirichlet energy. By expanding

\(\boldsymbol{f}\) in the eigenbasis, we obtain a graph analogue of

Parseval's theorem:

Theorem: Parseval's Identity on Graphs

For any graph signal \(\boldsymbol{f}\) with Graph Fourier Transform

\(\hat{\boldsymbol{f}} = \boldsymbol{V}^\top \boldsymbol{f}\),

\[

\boldsymbol{f}^\top \boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{f} =

\boldsymbol{f}^\top (\boldsymbol{V} \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{V}^\top) \boldsymbol{f} =

(\boldsymbol{V}^T \boldsymbol{f})^\top \boldsymbol{\Lambda} (\boldsymbol{V}^T \boldsymbol{f}) =

\hat{\boldsymbol{f}}^\top \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \hat{\boldsymbol{f}} =

\sum_{k=0}^{n-1} \lambda_k \hat{f}_k^2

\]

This identity shows that the Dirichlet energy of a signal equals the weighted sum of its

spectral components, where each frequency \(\lambda_k\) weights the corresponding

coefficient \(\hat{f}_k^2\). High-frequency components (large \(\lambda_k\)) contribute

more to the energy, which is why smooth signals have small Dirichlet energy.

Practical Computations

For large graphs (e.g., social networks with millions of nodes) seen in

modern applications, computing the full eigendecomposition (\(O(n^3)\)) is impossible.

Instead, iterative methods are used to find only the few

eigenvectors and eigenvalues that are needed (typically the smallest ones).

The spectral theory above assumes access to the full eigendecomposition of

\(\boldsymbol{L}\), but computing all \(n\) eigenvalues and eigenvectors requires

\(O(n^3)\) operations - prohibitive for graphs with millions of vertices. In practice,

most applications (spectral clustering, GNNs, graph partitioning) require only the few

smallest eigenvalues and their eigenvectors, which can be computed efficiently using

iterative methods.

-

Power Iteration: A simple method to find the dominant

eigenvector (corresponding to \(\lambda_{max}\)). Can be adapted (as

"inverse iteration") to find the smallest eigenvalues.

-

Lanczos Algorithm: A powerful iterative method for

finding the \(k\) smallest (or largest) eigenvalues and eigenvectors

of a symmetric matrix. It is far more efficient than full decomposition

when \(k \ll n\).

Modern Applications

The properties of the graph Laplacian are fundamental to many

algorithms in machine learning and data science.

Spectral Clustering

One of the most powerful applications of the Laplacian is spectral clustering.

The challenge with many real-world datasets is that clusters are not

"spherical" or easily separated by distance, which is a key assumption of

algorithms like K-means.

Spectral clustering re-frames this problem: instead of clustering points by distance,

it clusters them by connectivity. The Fiedler vector (\(\boldsymbol{v}_1\))

and the subsequent eigenvectors (\(\boldsymbol{v}_2, \dots, \boldsymbol{v}_k\))

provide a new, low-dimensional "spectral embedding" of the data.

In this new space, complex cluster structures (like intertwined moons or spirals)

are "unrolled" and often become linearly separable.

The general algorithm involves using the first \(K\) eigenvectors of the

Laplacian (often \(\mathcal{L}_{sym}\)) to create an \(N \times K\)

embedding matrix, and then running a simple algorithm like K-means on

the *rows* of that matrix.

We cover this topic in full detail, including the formal algorithm and

its comparison to K-means, on our dedicated page.

→ See: Clustering Algorithms

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs)

Many GNNs, like Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs), are based on

spectral filtering. The idea is to apply a filter

\(g(\boldsymbol{\Lambda})\) to the graph signal's "frequencies."

\[

\boldsymbol{f}_{out} = g(\boldsymbol{L}) \boldsymbol{f}_{in} =

\boldsymbol{V} g(\boldsymbol{\Lambda}) \boldsymbol{V}^T \boldsymbol{f}_{in}

\]

This is a "convolution" in the graph spectral domain.

Directly computing this is too expensive. Instead, methods like ChebNet

approximate the filter \(g(\cdot)\) using a \(K\)-th order polynomial:

\[

g_\theta(\boldsymbol{L}) \approx \sum_{k=0}^K \theta_k T_k(\tilde{\boldsymbol{L}})

\]

where \(T_k\) are Chebyshev polynomials. Crucially, \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{L}}\) is the

rescaled Laplacian mapping eigenvalues from \([0, 2]\) to \([-1, 1]\):

\[

\tilde{\boldsymbol{L}} = \frac{2}{\lambda_{max}}\mathcal{L}_{sym} - \boldsymbol{I}.

\]

This approximation allows for localized and efficient computations

(a \(K\)-hop neighborhood) without ever computing eigenvectors. The standard GCN is a

first-order approximation (\(K=1\)) of this process.

Diffusion, Label Propagation, and GNNs

The Laplacian is the "generator" of diffusion processes on graphs.

This isn't just a theoretical curiosity from physics; it's the

mathematical foundation for many GNN architectures and semi-supervised

learning algorithms.

For example, the classic Label Propagation algorithm for

semi-supervised learning is a direct application of this. You can imagine

"clamping" the "heat" of labeled nodes (e.g., 1 for Class A, 0 for Class B)

and letting that heat diffuse through the graph to unlabeled nodes. The final

"temperature" of a node is its classification.

The formal continuous-time model for this is the

graph heat equation:

Theorem: Heat Diffusion on Graphs

\[

\frac{\partial \boldsymbol{u}}{\partial t} = -\boldsymbol{L} \boldsymbol{u}

\]

The solution, which describes how an initial heat distribution

\(\boldsymbol{u}(0)\) spreads over the graph, is given by:

\[

\boldsymbol{u}(t) = e^{-t\boldsymbol{L}} \boldsymbol{u}(0)

\]

Where \(e^{-t\boldsymbol{L}} = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \frac{(-t\boldsymbol{L})^k}{k!} =

\boldsymbol{V} e^{-t\boldsymbol{\Lambda}} \boldsymbol{V}^T\).

This solution, \(e^{-t\boldsymbol{L}}\), is known as the

graph heat kernel. It's a powerful low-pass filter

(since high-frequency components \(e^{-t\lambda_k}\) with large \(\lambda_k\)

decay fastest). This process of diffusion is the formal explanation

for the over-smoothing problem in deep GNNs [2].

Many GNNs, like the standard GCN, are computationally efficient approximations

(e.g., a simple, first-order polynomial) of this spectral filtering [1].

More advanced models take this connection to its logical conclusion,

explicitly modeling GNNs as continuous-time graph differential equations [3].

This links the abstract math of DEs directly

to the design of modern AI models.

Insight: From Spectral Filtering to Message Passing

The spectral viewpoint (filtering via \(\boldsymbol{V} g(\boldsymbol{\Lambda}) \boldsymbol{V}^\top\))

and the spatial viewpoint (aggregating information from neighbors) are unified in GCNs.

Kipf & Welling (2017) proposed the renormalization trick:

\[

\tilde{\boldsymbol{A}} = \boldsymbol{A} + \boldsymbol{I}, \quad \tilde{\boldsymbol{D}}_{ii} = \sum_j \tilde{\boldsymbol{A}}_{ij}

\]

Replacing \(\boldsymbol{A}\) with \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{A}}\) (adding self-loops) serves two mathematical purposes:

it preserves a node's own features during aggregation, and critically, it controls the spectral radius.

Without this, the operation \(I + D^{-1/2}AD^{-1/2}\) has eigenvalues up to 2, leading to exploding gradients in deep networks.

The renormalization ensures eigenvalues stay within \([-1, 1]\) (with \(\lambda_{max} \approx 1\)), guaranteeing numerical stability

while maintaining the low-pass filtering effect.

Other Applications

- Recommender Systems:

Used extensively in industry to model user-item interactions as a graph, often leveraging matrix factorization on

the Laplacian or graph-based diffusion models to predict preferences.

- Protein Structure:

Foundational to bioinformatics, where GNNs (like those used by AlphaFold) model the 3D structure of proteins by

treating amino acids as nodes and using Laplacian-based graph convolutions to capture bond geometry.

- Social Network Analysis:

Continues to be the primary method for community detection (spectral clustering) and identifying network bottlenecks

(algebraic connectivity \(\lambda_1\)) at scale.

- Computer Vision:

Historically used for image segmentation and denoising via graph cuts (minimum cut problems, which are directly

related to the Laplacian quadratic form).

Core Papers for this Section

-

Kipf, T. N., & Welling, M. (2017). Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks.

International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

-

Li, Q., Han, Z., & Wu, X. M. (2018). Deeper Insights into Graph Convolutional Networks.

Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.

-

Poli, M., Massaroli, S., et al. (2020). Graph Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (GRAND).

Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).